A Day Like Any Other

The Blackfoot River, Sunday June 24th 2007

It was a day of kayaking that began like any other. Actually, that wasn’t true; for on this day, I was afraid. We were planning to run the lower Blackfoot river through Wolverine canyon. This is a run I had wanted to kayak since a few months previous. But make no mistake; the lower Blackfoot is solid class five whitewater and a decent step up for me and my comfort level. However, I had kayaked twenty out of the previous thirty days and twenty out of the previous thirty years and felt prepared for this step. Not to mention, this wasn’t my first time running class five rapids. I have taught kayaking for over five years and am an expert boater. That being said, I was still afraid. I wonder now if anyone else in my group shared my sentiments.

The put in to the river was a beautiful area. The river or creek was perhaps 30 feet wide and moving swiftly, but without any signs of the extreme whitewater to come. Wildflowers and green grasses swayed on the banks, while there were small chunks of black and brown basalt protruding from the sides as an indication of the canyon that was to come. I was the last of our group to put in and did my best to catch up with Justin Dayley so I would have some company for the beginning of the run. Jeff Doer, Justin Dayley, and I brought up the rear while Ken Ryan and Paul Abraszewski were about a hundred yards ahead.

The river quickly picked up speed and fury and I realized that I had an annoying problem of water leakage in my boat. After a series of class three waves I was forced to pull over and sponge out my boat. Justin also had to pull over to fix something. A few minutes later I saw Paul side surfing in a sticky hole created by a small pour over. He seemed to be having fun and he popped out of the hole just as I passed him. I found out later that he had been stuck and trying to get out for almost two minutes.

Perhaps ten minutes later we pulled off to the right to get out and scout the first major rapid of the day called Teller’s Tube. It was an awesome site. The rapid was perhaps 150-200 yards long and was divided into three parts. The first part was a chute, where the river constricted to half its previous width and dropped maybe 40 feet over the first 150 feet of length. This constriction and gradient, or steepness of the river, forced the water to astounding speeds and hence the creation of the name of the rapid. This initial section was broken up by four large hydraulics, also referred to as “holes”.

A river “hole” is a whitewater feature created when water pours over a rock placed below the surface of the water and creates a wave that doesn’t move. Some holes are friendly and fun to surf, while others are perpetually breaking and can be dangerous. A perpetually breaking hole can have a huge amount of recirculating water and as a result, can be very difficult to escape. Being caught in one of these is like being in a washing machine; a person will just be rotated through the breaking wave, sucked under, and rotated through again.

All the water in this steep initial section was flowing into and bouncing off a large boulder in river center. This rock created a large pillow flowing to river right with a huge hole at the bottom. The line was to go to the right of this rock and catch the eddy on river right just below it. This eddy was a must make move to get ready for the middle section of the rapid.

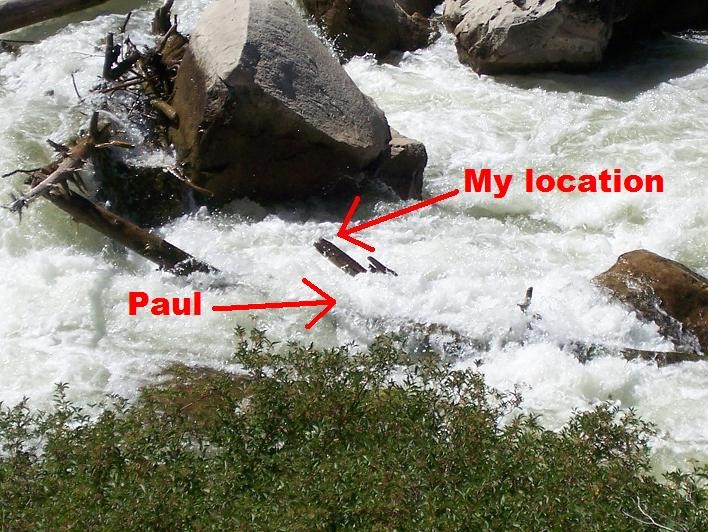

The eddy in river right (as seen above just below the boulder in the lower center) was so necessary because the middle section of the rapid was a log jam nightmare with wood traversing 95% of the river. The sneak route around the wood was to hug the right bank, duck under some bushes, and slip between some rocks to enter the third section of the rapid. However, to get to the sneak route, one had to first catch the above eddy.

The actual line down this section can not be seen as it is all the way on the right bank and underneath the bushes that block our line of site. The river left section is certainly runnable and not choked with wood, but is impossible to get to due to the upper section and where the water is pushing.

The third and final part to this rapid consists of setting up for and punching two giant holes. The second hole is around ten feet from trough to boil line.

After punching the second hole you can paddle around the third and the rapid is completed.

The scout and portage for this rapid is not easy as the banks are steep and composed mainly of chunks of sharp basalt talus rock. I made my way down to the bottom of the rapid to look at the bottom section first then made my way back up to the middle to have a closer look at the logjam. The sight I witnessed made me very uncomfortable. The truth is, this rapid is very runnable, providing the first part is done well. Like Jeff and Justin, I was leaning towards walking it but I hadn’t completely made up my mind. I figured, with all the whitewater ahead, this rapid would not make my day, but it sure could break it. That being said, I was waiting to see who ran it and how they did before making up my mind. Ken already had his boat on his shoulder and was carrying it down to the eddy just below the first section, so he could run the second half of the rapid. Paul was already on his way up to his boat to run the rapid. The only person Paul consulted about the rapid was Ken. Paul asked Ken about the first section, to which Ken answered, “it looks ok”, which it did. I know that Ken has regrets over not having said more to Paul about why he was portaging the top part. However, Paul did not ask, and I am of the opinion that the most convincing thing Ken could have said took the form of the boat already on Ken’s shoulder. We took our respective safety positions at various points next to the rapid. There I was, throw rope at the ready, positioned just below the critical middle eddy. Little did I know that I was about to witness and participate in the greatest horror of my life.

At this point my memory gets a bit fuzzy. Please excuse any discrepancies. I waited at my safety spot for five minutes before seeing Paul come into my field of vision. He was about at the second hydraulic in the initial chute. He looked good. This is when things went bad. It was either the second or third hydraulic that flipped him; from where I was standing I couldn’t be sure. He set for his roll as he cascaded down through these nasty hydraulics. I saw him pump twice while he was still coming down the initial chute. His rolls did not work; his boat was perpendicular to the current and his setup was on the downstream side; his paddle had no purchase. “Come on Paul, roll. Roll. ROLL!” I said to myself. He hit the slower water, just upstream of the logjam. I glanced just downstream of where he was; I saw in my mind the horrendous event that was about to take place.

Paul half-heartedly attempted his roll one more time, but failed. I saw the telltale sign of his boat twitching forward and backward. A sure indication that he was about to swim. I saw Paul’s head come up, and I watched in dread as less than a second later, Paul slammed into the logjam. The throw rope in my hands remained; useless. I was in shock; my brain was fried. “Oh no, oh no, oh no, oh no, OH NO! This isn’t happening. This isn’t fucking happening!” I thought. But yes, indeed it was happening. Paul was lodged between two logs that formed a V pointed downstream. Every couple of seconds I could see a flash of black from his helmet and a flash of red from his life jacket. His right arm was raised above the water level indicating that he was conscience. Paul’s head was under six inches of raging water. Ken, who was somewhere nearby, instantly tore off through the super dense ten feet thick layer of river willows that lined the banks. He was looking for, and found, a way to get to Paul. I climbed 15 feet up the bank, maybe for a better look, maybe to follow Ken. In truth, I didn’t know what I was doing. I turned around and went back to my original spot. At this point Ken was shimmying along the final log to get to Paul, and Jeff had joined me at my location on the bank. I don’t remember what Jeff was doing, but I asked him what I should do. He didn’t respond; so I said, “I’m going out there.” And I took off through the brush in a similar fashion to how Ken had done just moments before.

The way to get to Paul was not easy; more accurately it was fucking insane! The first move was to make a six foot jump from a rock to another rock then jump another eight feet into an eddy behind a boulder just upstream. After doing this, I grabbed the upstream rock quickly; before I was swept away and climbed up on it. The next move was to traverse eight feet of log that was covered with two inches of class five moving current. This brought me to a rock that was 20 to 30 feet from the river right bank and 20 feet downstream of Paul. From here I straddled the larger of the logs holding Paul and shimmied upstream towards Paul and Ken. I was scared out of my wits while doing this as the log I was on was covered with two to four inches of raging water and there were now log sieves just downstream of me on both sides. I’d be damned if I was going to let Ken struggle without help and Paul die alone. I must take a moment and thank Ken Ryan; I don’t know if I would have had the courage to go out there if Ken hadn’t first and demonstrated that it was possible. Going out there on that log is most certainly one of the salvations of my soul that I can take solace from. Now that I was out on a log with Ken and a stuck and rapidly dieing Paul, in the middle of a nasty class five rapid, the real work began.

Ken was on the log directly in front of Paul alternately trying to yank him up by his lifejacket and using a hand to try to create an air pocket for Paul to breathe under the six inches of water that poured over his head. Paul was still alive at this point. He was trying to help make an air pocket for himself and pull himself out by grabbing Ken. Ken told me later that Paul was responsive when he had arrived; Paul said a few things that were indistinguishable. Ken told me to try to get to the other side of Paul and make an air pocket while he tried to pull him out; somehow I managed to crawl around Ken and Paul and sit on the smaller log that was trapping Paul. I stayed on by hooking my leg underneath the log into some deadwood that was also trapped in the sieve. I brought my hands to the front of Paul’s helmet and tried to siphon the rushing water away from Paul’s mouth enough for him to breath. I could feel water splashing around between my hands. My air pocket wasn’t working. I felt like I was killing Paul. We changed tactics. Together Ken and I gripped the front and the back of Paul’s lifejacket and heaved. And Heaved. And HEAVED, until I thought I would fall off my precarious perch. Do to the nature of where I was sitting, with half my body in the same water that was trapping Paul, and nothing to push off of with my feet, I had no leverage, and could not lift with near enough force that I thought I should. I kept telling myself, “pull harder David; Damn it, Pull Harder!” At some point during these initial attempts Paul’s hand came up and briefly touched my arm. Then he lost consciousness; then he was gone. I did not realize that he had died at this time. While we were trying in vain to pull Paul free, his lifejacket began to slip up on his body. This scared me because I knew that without Paul’s lifejacket, there would be nothing to hold on to.

I wanted to cry. I wanted to fall apart and huddle in a ball. I knew something big was happening that would change my life. I didn’t know how to handle it. But every time I felt like I was close to breaking down, I steeled myself and shoved my fear and pain in to the back of the head. I had a job to do. Paul and my friends needed me now; there was time to break down later. After failing to pull Paul free, Ken suggested that we try to push him under the log. I was horrified, but without other options. I pushed him down with my hands, but I could hardly get him a foot below the water. Also I couldn’t lean over very far without falling into the deadly water that had trapped my friend. So I put my feet on Paul’s chest and tentatively stood on top of him. It was sickening. Paul would bob in the water a bit, but he wouldn’t truly submerge; he was beyond stuck. I suspect that there was no going underneath this log. I believe that the whole area in front of Paul was choked with debris from riverbed to water level. There was no “underneath”. At this point we received a rope from the bank. I don’t remember who caught it.

Justin and Jeff were on the bank at the ready, rope in hand. Ken quickly clipped the spectra rope to the closest shoulder strap of Paul’s life vest. Ken and I lifted together while Justin and Jeff pulled from the shore. Paul didn’t move an inch. We tried again, but I knew what we were attempting was futile. I called to the shore that we needed a Z-drag. I want to make clear how difficult it was to communicate with the bank. Even though they were, maybe, forty feet away, with the background noise of the water and my own head, it was very difficult to hear them. After the third attempt at communication, they understood me. It took a couple minutes for them to rig up the anchor and set up the rig. It was these periods of down time that were the worst. This is when my brain became active again and started to encompass the awfulness of what I was witnessing. We had long since stopped trying to create an air pocket for Paul. He had long since stopped moving. His head was clearly underwater as it had been for the past I don’t know how long. His body behaved like an extremely heavy rag doll.

The passage of time was extremely fast and at the same time crawled like it had nowhere to go. When the Z-drag was ready, Ken and I prepared to lift Paul. The Z-drag pulled and once again, Ken and I lifted. The men on the shore had the hearts of grizzly bears and they applied thousands of pounds of force to the line, and yet Paul still did not budge. I heard some yelling from the shore and I thought I heard Jeff say that they needed to cut the line. I found out later that we had snapped a spectra rope with a 2000 pound tolerance. The rope was cut and it hurried downstream.

“Rope!” Jeff said, and he threw it. I caught the bag perfectly as I sat perched on the end of my log. The impact of the rope almost knocked me off. I yelled at the riggers to move the Z-drag anchor upstream. The problem we were having with the Z-drag was not a problem of insufficient force; instead it was an issue of incorrect angle. We were attempting (due to a lack of other options) to pull Paul through a log that a tractor would have been hard pressed to move. I will try to illustrate.

The log that held Paul in place on our side of the river was placed at an angle nearly parallel to the current. Justin and Jeff, on river right, were able to increase the angle in the z-drag line to around 120 degrees to the current. However, since the log in question went past Paul upriver for another 10 feet, the shore team would have had to be directly behind Paul for this approach to work. This would have put them in the middle of the river. (Note: despite my poor artwork, six inches of water were flowing over Paul’s head at the time.)

Somewhere in the back of my mind I knew that our current approach would not work and that we had to do something else to get Paul free, but I had no idea what. I kept telling myself to think! Think of a solution! But none came to me. At this point Ken told me that he was going back to the shore to help Justin and Jeff with the rigging. There I sat, alone, on my perch, futilely holding onto the shoulders of my friend Paul. It was a strange feeling; holding him. He was completely limp now and the back of his neck was very pale. These moments when we were not actively engaged in freeing Paul were difficult; without action I had only thought, and my thoughts were not good ones. Soon the shore signaled me that they had the new rig set up and were ready to pull.

Within a few seconds of the new rig being set up I watched in shock as Paul’s life jacket began to rip off of him. I thought, “What the hell? Aren’t these things built to withstand these sorts of rescues?” The truth is that nothing is built to withstand a rescue like this one. I told the guys on shore to stop pulling, which they did. I needed some time to rig a piece of webbing around his chest. I thought briefly about how to do it when his chest was over a foot beneath raging water. The only thing I could come up with was a girth hitch. I knew that the applications of this knot in rescue limited to the use of setting up anchor and is never used to attach to a person because of it’s propensity to become too tight and injure the rescuee, but at this point I was desperate. I had no idea how long Paul was out and had no ideas what other way I could attach the webbing to Paul that wouldn’t come off or over his shoulders. All I knew is that we had to get Paul out quickly.

I was perched on the end of a two foot section of log.

I had my left leg dangling over the log on the same side Paul was. My right leg straddled the opposing side and was locked around my left leg to keep me in place. My left foot was somewhere underwater next to Paul’s left shoulder. I was actively pushing on him for balance. I leaned over as far as I could with the webbing in my hands. Try as I might, I could not get close enough to wrap my arms around Paul’s chest. Every time I would reach around Paul, the intensity of the water was such that I couldn’t even find my own hands. It is difficult for me to describe the precariousness of my position. I was fully aware that my location was neither stable, nor was my position dependable. I knew that if I fell into the water, my body would be pinned right behind Paul’s. It took me a few minutes, but I eventually secured the girth hitch. I did this by letting go of one end of the webbing, letting it float downstream, then reaching around Paul to grab it. When the hitch was secured, I carabined it to the Z-drag line. When that was accomplished, I yelled at the shore to pull.

I saw the error of my work immediately. The Z-drag was still clipped to Paul’s torn life vest. The tension on the line continued to pull on the PFD and not on the webbing around his chest as I had intended. Once again I yelled at the shore team to give me slack. After some reaching and more frustration at how much time the entire process was taking, I managed to unclip the PFD and clip in the end of the girth hitch. Once again I told the shore crew to pull. They pulled and suddenly there was an immense amount of tension on the line and on Paul. He didn’t budge an inch. It was like trying to pull him through the log that was holding him. Worse yet, as the tension increased, Paul’s left arm flopped up over his head and the girth hitch slipped over his arm and relocated around his neck. I had the sudden grisly image of watching Paul’s head get torn off. I screamed for the shore crew to stop.

Somewhere during these attempts the riggers on shore tried moving the Z-drag anchor upstream to achieve a more functional angle of pull. After spending more precious minutes readjusting the girth hitch, we tried again to pull Paul free. Again the girth hitch slipped over his arm. I leaned over once again to replace the girth hitch around Paul’s chest. This is when something weird happened. I fell. I was leaning over, trying unsuccessfully to reach around Paul. I was so tired. The fatigue weighed upon me like a heavy dark cape. All my movements were slow. My hands were shaking and I was cold from being splashed with the angry waters of the Blackfoot. As I was leaning over, my left leg slipped and came unlocked from my right leg. In slow motion I began to fall. I remember the frothy white surface of the water coming up to meet me. I thought “oh my god! I’m going in.” I was going to fall directly upstream and behind Paul. I was going to be trapped, not by the logs, but by Paul’s body. I was going to die. I reached out. Then, suddenly, I was moving away from the water’s surface. Then, I was upright and settled, on top of my log. I didn’t know what happened. I couldn’t think about how close I came to joining Paul or how I managed to avoid it. We still had work to do, and I was needed.

I don’t know if I called for help or the shore crew just realized that I needed help out there, but I saw Ken break away from the group and start the dangerous trip out to where I was. I was dazed from my recent brush with a watery death. I retreated from my log perch to the resting rock just downstream. I sat down; I was so tired. I wanted to lie down right there and sleep.

It wasn’t long before Ken got to where I was resting and the work began anew. I returned to my perch spot and Ken was just downstream of Paul and myself. We attached the girth hitch again and it was much easier because I was able to just hand the ends to Ken for him to wrap around Paul’s chest. We had Justin and Jeff, the shore team, pull once again. But again the incredible force of the Z-drag pulled on an object that was neigh unmovable and the strap pulled over Paul’s shoulder. I couldn’t figure out why this wasn’t working; the hitch should have held tight around his chest. But I could see that we had damaged Paul’s shoulder in the rescue. His arm was no longer sitting right at his side.

Ken and I had reached a point of exasperation. We had to get him out, and soon. I had some idea that he might somehow still be alive at this point. I was completely unaware of the passage of time. The truth is, I had known for a while of how to successfully attach Paul to the line, but it was too horrible to contemplate. I asked Ken, “Are we doing a rescue? Or are we now doing body recovery?”

“Body recovery,” Ken said.

“I know how to tie him,” I said, “grab his arms and hold his hands.” My heart was broken. I knew that by tying the webbing first around one wrist, then around the other, and finally tying both wrists together, the friction created would make it near to impossible for the knot to slip. I felt nauseous. I didn’t want to do this. I had pictures of Vietnam prisoners of war being hung from their hands in some dirty hopeless cell floating through my head. This was no way to treat a person; much less a friend. But dammit, we were out of options! What could I do? What could we do? I was desperate. Ken and I were efficient. We tied Paul well. He would not slip out this time. Again we told the shore crew to pull.

We encountered the same problem as before. The rope was trying to pull Paul through the log holding him in place. Only this time Paul’s arms were being violently pulled over the log. Ken and I tried to lift Paul vertically while the shore team pulled. It was like trying to lift a Buick. My mind reeled as I watched Paul’s arms be nearly torn from their sockets. I yelled for the shore team to stop pulling. “What do we do?” I asked Ken, “This will not work. We need to change the direction of travel of the rope.”

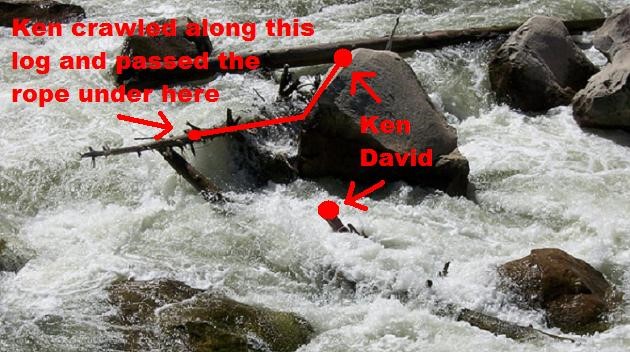

“What if we could get the rope underneath that log instead of over it?” Ken asked.

“I don’t know, maybe,” I said with exasperation.

Ken surveyed the river and the placement of the rocks and said, “Let’s try it.” Then he took off. Ken was fearless in the way he jumped from rock to rock and rock to eddy. I don’t think I could have done what he did. This was his path.

Ken got to the rock upstream of me and I unhooked the line to Paul and let it float downstream. The shore team pulled the line in and threw it to Ken. Ken fearlessly crawled out on a log that was perhaps four inches thick and directly upstream of Paul and the hydraulic forces that had crushed him. Ken then fed the throw rope under this log and presented us with a new vector of pull with which to attempt to dislodge Paul.

Ken tossed me the rope and I carabined it to Paul’s tied wrists. I yelled at the shore team to pull again and while Ken made his hazardous climb back to our position, I waited in anticipation for the results of this new approach. It was sickening. The ease at which Paul came free defied the intense labor that the four of us had spent the last hour engaged in. I had pulled on Paul to within an inch of my life; I was mentally and physically exhausted and I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. But by getting the Z-drag rope underneath the river right log that held Paul, he came free so effortlessly that the Z-drag was probably not necessary.

Paul’s body came out, pulled upstream, and began to pendulum to the shore. I remember standing on my “resting rock” and watching the spectacle, all emotion drained from my being. He appeared to move through the water like he was flying with his arms outstretched in front of him, or perhaps like a sturgeon, hooked, and being pulled in. I could see how pale he was, even through the water. Paul was naked from the waist down. The force of the water had removed all of his clothes, his booties, and over the course of the rescue, even his life jacket. The only thing he still wore was his paddling jacket. I marveled at the strength and callousness of the river. I sighed with relief and began the perilous crawl back to the river bank. Now that the urgency of saving my friend was passed, I was terrified of where I was in the river. I hesitantly made the moves that I had to make to get back. I didn’t feel capable of maneuvering myself to shore, but I knew that there was no rescue for me; there was no other way to get to shore then by my own strength and agility.

As I closed in on the river right bank I heard a commotion coming from the other rescuers. The operation was not over, Paul was not yet free. I sighed in exasperation, my strength was failing me. When I got to the right bank, I saw what had happened. With no flotation on Paul, he had sunk to bottom of the river. As Paul was swinging to the right bank, the rope he was on had gotten caught beneath some rocks. Paul wasn’t more than twelve feet from the bank although we could no longer see him. I could see the rope emerge from the water perhaps five to ten feet up river from Paul. I began to have desperate thoughts at this point. I just wanted this to be over. We had worked hard, we deserved for this to be over. I seriously entertained the idea of jumping in to where Paul was and grabbing the rope up stream of him. I knew I could free him this way. I knew it! Then I could ride the rescue rope back as it swung to shore. Better sense prevailed before I acted on this thought.

The riggers attached a carabineer and a second rope to the taught line that ran to Paul. Ken dared to return to a position close to where we were before. Ken was on the river left side of Paul and able to apply a perpendicular pull to the rope holding Paul. The stuck rope came free immediately and the riggers guided Paul to an eddy near me. Paul was face down bobbing in the water. I seem to recall Ken throwing Paul on to his back and lifting him, while I tried to help by lifting Paul’s legs. Paul’s skin was the color of white canvas; his flesh had the feel and look of plastic. We got Paul onto the bank and turned him over. The ravages of the rescue were plain to see. We had abused poor Paul significantly while trying to get him out. Dark purple bruises lined his wrists arms and shoulders. Paul had cuts on his face and neck. He lay there on the black basalt rock, surrounded by dark green brush with his eyes open; lifeless and staring at nothing. I was overcome by an intense morbid curiosity. I poked at Paul a couple of times. I am not sure what I was seeking by doing this. His flesh felt hard but malleable. It was kind of like poking plado or silly putty. I had to restrain myself from any further displays of my strange curiosity.

Ken was discussing ways of getting Paul to the top of the canyon when Justin said some very simple, but powerful words, “It’s ok to ask for help. We have done well. We got him out and to the bank of the river. It is ok to ask for help now.” Ken and I were reluctant to pass this job onto anyone else. Justin continued, “You two were inspirational out there. No one could have asked more of you. It is time to get help.”

Thus began or painful and silent journey to the top of the canyon. This was no easy physical task for the canyon walls loomed 500 feet above us. The trail out consisted of climbing a steep talus slope to the canyon rim. Sharp unstable rocks combined the with the unworldly fatigue that we all felt made the trip out surreal and dangerous. We decided to take our boats and gear with us on the climb. It was grunting; it was struggle; it was slow. Justin lagged behind as his damaged ankle had been more than overworked this day. I felt energy high within me that I didn’t quite know how to handle. I knew that so long as I stayed busy and suffered through physical exertion I wouldn’t have to think of the day’s horror. As soon as I got my boat near the top I ran down to help Justin with his. When all the boats were at the top, the day, which had moved so quickly up until than, slowed to a crawl.

The put-in truck was retrieved and we drove to a place where we could get cell service to call search and rescue and our respective loved ones. I wanted to call my father and go through the complete mental break down that I had sought since the accident, but Justin wisely warned me that it was not yet time for that.

Search and rescue showed up in the form of one fat sheriff. We told him that we needed 12 strong men and a backboard, but he couldn’t take our word for it. (Despite the fact that we were the most qualified swift water rescue team assembled in all of eastern Idaho) The fat sheriff had to go look, then he called his boss who had to go look. We were offered the choice to help bring Paul’s body to the canyon rim or to return to Pocatello to bring the news to Paul’s wife. The obligation that we felt was to not leave a man behind. We elected to stay. Finally about four hours later we were back on the canyon bottom with 12 strong men and a metal stretcher. I remember laughing when a few guys from the search and rescue team were freaked out by a rattle snake near Paul’s body. I took a stick and shooed it away. I still felt like I hadn’t done enough; I still felt like I had failed; failed Paul, failed my companions, failed myself. I needed to do more. Everyone present rotated in and out of the different carrying positions on the stretcher. My muscles burned and my joints ached, but I never left my position. I remember feeling that the Search and Rescue guys were a bit too jovial and upbeat for my liking. When Paul’s body was at the rim, we left.

I drove back to Pocatello with Ken. He agonized over not saying something to Paul when they passed each other while scouting the rapid. I reaffirmed that it was Paul’s decision and not his fault, but I knew it would haunt Ken for a while to come. As we approached Paul’s house and the impending encounter with his wife, I began to get nauseous. What would I say to her? How should I act? Would she blame us? As the left turn approached, I felt a burning urge to yank the steering wheel to the right or to ask Ken to stop and drop me off. But I did not, and soon we were parked. The four of us got out of the trucks and turned towards Paul’s house. At that moment, every fiber of my being wanted to be somewhere else. I steeled myself internally and began to walk across the street. It was the hardest thing I have ever done.

Afterword

The most common question I hear when I tell people about this story is “Why are you writing it?” The short answer is Honor. Honor to Paul and his final struggle on this earth; honor to my brother rescuers who risked their lives to save a friend who was unsavable; honor to myself. This is a story worth telling; an educational look at river rescue combined with an intense look into some of the driving forces that emerge when life and love are on the line.

I began to write this story as part of a cathartic process intended to help me heal and find closure. As time passed, I visited this story less and less. In the end, however, I decided that, among a lake of unfinished projects, if I am at all to be a man of conviction, this project would be completed.

What have I learned from this experience? I have learned that I am a good man to have in a bad situation. I have learned that sometimes all the strength, training, and effort of man cannot prevent the inevitable. Before this event, I thought that if I was truly committed to an outcome of an event, I could make it happen. I truly thought I would be able to save Paul that day. I was wrong. On this day I learned about pain, not my pain, but Lee’s, Paul’s wife. The agony of loss I have seen in her eyes frightens me. I have not felt this pain, nor do I wish to. I am humbled by it. Some of the other things I’ve learned just can’t be put into words.

I hear Paul talking to me from time to time. When I perceive some misfortune in my life and start feeling sorry for myself, I hear his Polish accent saying, “I think it’ll be ok.” There is a smile in his words and the utter belief that they are true. That was how Paul was; the positive outcome of every situation Paul found himself in he absolutely accepted as fact. Paul was an amazing man. He gave all of himself to anyone he happened to be with. He was a world class cardiologist and an even more incredible husband, friend, and son. Paul Abraszewski’s life was a life worth remembering. I think his death is worth remembering as well.

Dedication

In memory of Paul—Thank you for teaching me how better to live.

To the rescuers—Heroes…

To Lee—No one can say why we must suffer so in this life. I will always be there to help.