Get your ya ya's out and be a kid again when you explore sandstone canyons and Anasazi ruins along the beautiful San Juan River during out April Spirit Quest Rafting Trip!

The average person uses around 70 to 80 rolls of toilet paper a year. That is a lot of trees. But have no fear, there is a solution! Read on for the most eco-friendly, biodegradable, and rear-end pleasing toilet paper alternatives.

I remember the first night camping under the stars. I remember the sound of the river and the feel of the sandy beach. What stands out the most, however, was the night sky! Wow, what a spectacle those stars were.

The word courage comes from the French word coeur, which means heart. To have courage is to have heart. Courage is a choice we all must make for ourselves. It is a choice to step boldly into the future despite the chance of being poor, alone, or meaningless.

I don’t fear cliffs, steep slopes, mountain lions, or bears. I fear silence. I fear stillness. I leave today on a 10 day silent seated meditation retreat and I am terrified of the deep contemplation of reality I will encounter in this time.

Five Survival Tips That Might Keep You Alive… Take A Survival Kit With You: Most kits have the basic necessities to keep you alive. Buy one or learn to make your own with Fire Heart Adventures

The following was adapted from Kyle Eschenroeder's blog Ten Overlooked Truths About Taking Action. See the original blog here.

Take Action

Nine Steps to Moving Forward with Your Dreams

1. Action is Cheaper than Planning

Do you know why the Wright Bros. beat out all the mega-corporations they were competing with in the race to taking the first flight? Action.

Robert Greene explains in Mastery that the Wright Bros. had a tight budget and were forced to make small, cheap tweaks to each model. They would fly a plane, crash it, tweak it, and fly it again quickly. The corporations had budgets that allowed them to go back to the drawing board (i.e. abstraction) with each failure. They spent a ton of money and time on each redesign.

The Wright Bros. had a hundred test flights in the time it took these big corporations to complete a handful. Every test flight taught lessons – the one who failed fastest gathered the most information. The key is to make the tests cheap and quickly make small improvements.

This applies to everything. Especially your life.

Planning has paralyzed me time and again. I was taught to always have a plan before taking action.

Most of the time, planning is procrastination. It’s based on theory. It’s going to be wrong.

Plans are useless without action.

2. Action Allows Emergence

Taking action creates possibilities that didn’t exist before.

We always look out at our future from the place we’re standing. Yet we forget that this is only one spot.

Imagine walking in New York City. All you can see are skyscrapers, neurotic humans, and taxis. You turn down the next street and you’re looking out into the trees of Central Park.

A completely new possibility has emerged.

If you’re obese then you probably don’t see a possible future where you’re fit. But, after three months of working out and eating well there will be a possible future of physical fitness that didn’t exist before.

These possibilities seem to “come out of nowhere” but they actually come out of action.

If you’ve only failed then it’s impossible to see the possibility of success. The trick is to keep trying. That next step might be the key to a better future — you just can’t see around the corner yet.

3. Inaction is Scarier

Inaction tempts us because it’s slow.

We don’t consider refusing to choose to be a choice. We think we’re safe if we don’t expose ourselves to failure. We don’t appreciate the consequences of inaction because they are slow, chronic, and less obvious. That’s what makes them worse.

You don’t get to escape pain. The pain that comes with action is acute, gives you scars, and makes you grow.

The pain that comes from inaction is low-grade, makes you soft, and makes you decay.

4. Motivation Follows Action

I don’t feel like working out until I’ve been at the gym for 15 minutes. I’m too tired to have sex until we’ve started. I don’t want to go to the party until I’m there.

Motivation (and passion) will follow you if you have the balls to go without them.

5. Action is an Existential Answer

I’m a professional when it comes to existential crises. I’ve spent a large portion of my life in “what is the meaning of my life?” mode. I’ve come up with a lot of clever answers. Some of them even felt original.

The only one that ever really works is disappointingly simple: do something.

The meaning of my life cannot be summed up in a pithy quote or even the most complete philosophy.

It is impossible to give yourself a satisfying purpose in the abstract.

It is only in the flow of action that life can make sense. There are no abstract ideals there, just life.

6. Action Creates Courage

“Courage is not something that you already have that makes you brave when the tough times start. Courage is what you earn when you’ve been through the tough times and you discover they aren’t so tough after all.” -Malcolm Gladwell, David and Goliath

Every time I sit on my ass and do nothing to promote Fire Heart Adventures, I become terrified of my impending failure. Every time I sit down and create content, develop a new adventure, or go into the wilderness to search out new destinations for myself and my student, I think “This venture cannot lose”.

7. Action Beats the Odds

“Spartans do not ask how many are the enemy but where are they.” –Plutarch, Sayings of the Spartans

The perfect plan doesn’t exist.

The great Warren Buffett biography The Snowball shows that Buffett had no grand plan when he was younger. He just knew that he wanted to make a lot of money. There was no early master plan, just a powerful urge and the willingness to take opportunities as they came.

You don’t need to know if it will work (you probably can’t know), you need to try and find out.

Your obstacles are yours to face. It doesn’t matter how they compare to the obstacles in history or those of your peers. It’s a waste of time to consider anything except how you will overcome them.

8. Action Makes You Humble

Teenagers think they know everything because they haven’t tested their mettle. They don’t know anything and so they feel like they know everything. They are just beginning to learn about theories and possibilities. They haven’t done anything so they feel like they can do anything.

After the young realize they can’t do everything they become disillusioned. They stop trying anything. They fall into inaction. This is why most adults end up so dull. They don’t do anything because it’s probably going to fail. They mistook early failures for a sign that they should stop trying.

That’s why they’re bored, depressed, and lethargic.

Instead, our failures should strengthen us. We should recognize that failures are how we learn and grow.

Just ask, “What would Leonidas think?”

9. Action Isn’t Petty

Action isn’t concerned with opinions, it’s dedicated to reality.

Action doesn’t leave room for gossip.

Action couldn’t be small if it tried.

You are not petty, nor are you small. Take the action that is reflective of your highest self and highest potential.

Spirit Quest Rafting

April 25th – 28th 2015

Overview

The spirit quest is a four day all inclusive rafting trip in the San Juan canyons of Southern Utah. This adventure is one of exploration and personal expansion. In addition to rafting, there are daily opportunities for hiking, archeological discovery, and yoga and meditation at sacred sites. All meals are fresh and organic.

Where: The upper canyon of the San Juan River from Bluff to Mexican Hat, Utah. Total river distance: 26 miles.

When: Guests should arrive in Bluff the morning of April 25th or the evening of April 24th. The river put in is on April 25th. River Take out is the afternoon/evening of April 28th.

Guides: Kay Harris of Canyon Expeditions and David Michael Scott of Fire Heart Adventures.

Cost: 850 dollars covers all food, group gear, rafting, guiding, and instruction on this trip. A 200 dollar non-refundable deposit is required to hold you place. Full payment before April 1st.

Canyon Expeditions

Canyon Expeditions is owned by Kay Harris, who has over 30 years of experience on the Colorado Plateau. Based in Cedar City, Utah, Canyon Ex runs river trips on the San Juan as well as backcountry trips throughout the desert Southwest. All guides are licensed and trained in Advanced First Aid and CPR.

Our boats are 16' and 18' industrial rafts, capable carrying a full kitchen, fresh water and other gear necessary to make a comfortable and enjoyable experience. The rapids are not difficult, and with a little instruction, you will be able to successfully navigate the river in an inflatable kayak. We camp on sandy beaches along the river's edge. Lands south of the river form the northern edge of the Navajo Nation.

David Michael Scott

David Scott has been practicing yoga and meditation for over ten years. He has spent time studying vipassana meditation in a Buddhist monastery in Northern Thailand and lived for a few years in the Amazon rainforest as a Peace Corps Volunteer. Before finding yoga, David was passionate about learning survival and aboriginal skills in the desert of Southern Utah. As a youth, David grew up kayaking and rafting. He began teaching kayaking at age 18. The nature of this trip is a combination of David’s passions: the river, the desert, and yoga.

A Community Driven Experience

We believe that the greatest community is created when the entire group shares in the labor and camp chores. This includes all the guests and raft guides. What this means is that we are all responsible for helping to load and unload the rafts each day. Each guest will help cook and clean for two to three meals during the trip. While this might sound a bit strange on an all-inclusive raft trip, it is better this way. When we work as equals in this community, what we build will be beautiful.

Meals

Our meals include quality meats, specialty cheeses and a variety of fresh vegetables and fruit--many of which come from our organic gardens in Bluff as well as regional Colorado Plateau farmers. We can accommodate most eating preferences and dietary restrictions including vegetarian options and would be happy to discuss a specialized menu for any trip.

Our day trips include a delicious salad or sandwich layout as well as snacks and plenty of water. On multiple day trips we serve hot coffee and tea, hearty breakfasts and salads and sandwiches for lunch. Our dinners might include grilled salmon or steaks, abundant stir-fries and pasta dishes and homemade tamales.

Supplies

We supply and row the boats, which include 16' and 18' industrial rafts. If you would like to paddle your own craft, ask about our inflatable kayaks. We provide all the food, snacks, and non-alcoholic beverages, in addition to the kitchen, stoves, plates, cookware and cups.

In short, we provide all the gear except for your personal gear. Upon booking a trip, we'll send you a list of personal gear to bring on your trip. We provide waterproof bags for your personal gear, as well as watertight boxes for your camera and other items.

If you don't have your own sleeping bag, pad or tent you can rent them from us. Our fleet of tents and sleeping bags is new and sleeping bags are washed after each use. If you or members of your party need to rent tents, sleeping bags or pads, we ask that you reserve them in advance.

Trip Summary

This four day rafting trip provides ample time for yoga and meditation as well as exploring Anasazi ruins. Our trip leader, Kay Harris, will provide expert interpretation of the upper canyon's rock art, cliff dwellings and textbook geology. David Michael Scott will guide the yoga and meditation curriculum in the mornings and the evenings. The days will be filled with rafting, hiking, laughter, and fun.

This 26-mile journey affords a closer experience with the Upper San Juan River. In addition to visiting ancient rock art sites and cliff dwellings, we'll have the option to hike to the top of Comb Ridge for its commanding view of the surrounding landscape. We'll travel through a quarter of a billion years' worth of colorful rock formations, making camps in spectacular corners of the canyon.

This is an all-inclusive rafting trip. Healthy meals and all group gear will be provided by the outfitter, Canyon Expeditions. Guests must provide their personal camping gear, although we have lots of extra stuff (sleeping bags, tents, etc.) if you need it. Guests are also responsible for transportation to and from the river and any alcoholic beverages they want to bring along.

Detailed Itinerary

Night Before Departure:

You will meet with Canyon Expeditions in Bluff at 7:00 p.m. for the prelaunch orientation. Your trip leader will hand out waterproof bags and boxes. We can also supply sleeping bags, pads and tents, but be sure to reserve them in advance with our office.

Day One: For those who camped the night, we will begin the day with some light Sun Salutations followed by a short meditation. We will then depart for our launch ramp and the river put in. The float begins as the river meanders past orange and black streaked sandstone outcroppings.

Soon the boats pull into shore and we take a short walk to a site once inhabited by ancient desert farmers, the Anasazi. Large oval steps are carved into the cliff wall and petroglyphs appear around every corner.

Downriver a short distance, we will enjoy lunch under the cottonwood trees at the famous Butler Wash petroglyph panel with plenty of time to examine this extensive group of mysterious images.

After lunch we may observe additional rock art panels across the river on the south bank, or we may explore panels near our camp a few miles downstream.

Camp is pitched in the late afternoon on a sandy beach amongst the cottonwoods and giant sagebrush. Our community will prepare a healthy dinner. After which we will have an optional yoga and meditation practice. Sunset and campfire, then it's off to sleep in a tent or out under the stars.

Day Two: First person to rise puts on hot water for tea and coffee. We will begin the day with a yoga practice and meditation.

After breakfast the group walks to River House, an 800-year-old cliff dwelling. You can spend time amid the round walls of a kiva where dried corn cobs remain with bits of pottery. This hike can be extended by exploring the nearby bench lands for more sites and another large kiva.

We'll then hike a short distance downstream to observe a great kiva and associated surface sites, and then a hike up San Juan Hill. This steep route was chiseled along a diagonal opening in the cliff by the famous Mormon "Hole-In-The-Rock" expedition in 1880. The views from its top--also the top of Comb Ridge--are incredible.

We will have more time this evening for a deeper yoga practice followed by a dharma session.

Day Three: Morning Sun Salutations while sheep graze in the background?

After breakfast we'll pack the boats for a short float downstream to Chinle Wash, where painted rock art and cliff dwellings hide among the rock alcoves. Author Tony Hillerman calls Chinle Wash "Many Ruins Canyon" in the mystery novel Thief of Time.

At Mile 9 the river enters the "anticline" and the canyon walls rise up dramatically. The river narrows and the pace quickens as small riffles and rapids rock the boats.

Camp is made deep within the canyon where the limestone walls are full of fossils and a lively current murmurs against the rocks.

The evening yoga practice will be dedicated to vipassana meditation.

Day Four: Last morning yoga of the trip! There is time after breakfast for fossil hunting. An undulating pattern to the rocks reveals the presence of "bio herms." Porous mounds in an ancient shallow sea, they act as a reservoir rock to capture oil.

Desert bighorn sheep may appear along this stretch. The rocks tilt and canyon walls diminish as Mexican Hat Rock comes into view, a large red slab balanced on a small pedestal. The vivid reds and grays of the anticline zig-zag across the eastern horizon, a Navajo blanket of stone.

The journey ends by 2 or 3 p.m. at the boat launch in the town of Mexican Hat, where Canyon Expedition vans will transport you back to Bluff.

Note:

Itineraries can vary depending on the river level, weather, group ability and interest. All hikes, yoga, and meditations are optional.

A Day Like Any Other

The Blackfoot River, Sunday June 24th 2007

It was a day of kayaking that began like any other. Actually, that wasn’t true; for on this day, I was afraid. We were planning to run the lower Blackfoot river through Wolverine canyon. This is a run I had wanted to kayak since a few months previous. But make no mistake; the lower Blackfoot is solid class five whitewater and a decent step up for me and my comfort level. However, I had kayaked twenty out of the previous thirty days and twenty out of the previous thirty years and felt prepared for this step. Not to mention, this wasn’t my first time running class five rapids. I have taught kayaking for over five years and am an expert boater. That being said, I was still afraid. I wonder now if anyone else in my group shared my sentiments.

The put in to the river was a beautiful area. The river or creek was perhaps 30 feet wide and moving swiftly, but without any signs of the extreme whitewater to come. Wildflowers and green grasses swayed on the banks, while there were small chunks of black and brown basalt protruding from the sides as an indication of the canyon that was to come. I was the last of our group to put in and did my best to catch up with Justin Dayley so I would have some company for the beginning of the run. Jeff Doer, Justin Dayley, and I brought up the rear while Ken Ryan and Paul Abraszewski were about a hundred yards ahead.

The river quickly picked up speed and fury and I realized that I had an annoying problem of water leakage in my boat. After a series of class three waves I was forced to pull over and sponge out my boat. Justin also had to pull over to fix something. A few minutes later I saw Paul side surfing in a sticky hole created by a small pour over. He seemed to be having fun and he popped out of the hole just as I passed him. I found out later that he had been stuck and trying to get out for almost two minutes.

Perhaps ten minutes later we pulled off to the right to get out and scout the first major rapid of the day called Teller’s Tube. It was an awesome site. The rapid was perhaps 150-200 yards long and was divided into three parts. The first part was a chute, where the river constricted to half its previous width and dropped maybe 40 feet over the first 150 feet of length. This constriction and gradient, or steepness of the river, forced the water to astounding speeds and hence the creation of the name of the rapid. This initial section was broken up by four large hydraulics, also referred to as “holes”.

A river “hole” is a whitewater feature created when water pours over a rock placed below the surface of the water and creates a wave that doesn’t move. Some holes are friendly and fun to surf, while others are perpetually breaking and can be dangerous. A perpetually breaking hole can have a huge amount of recirculating water and as a result, can be very difficult to escape. Being caught in one of these is like being in a washing machine; a person will just be rotated through the breaking wave, sucked under, and rotated through again.

All the water in this steep initial section was flowing into and bouncing off a large boulder in river center. This rock created a large pillow flowing to river right with a huge hole at the bottom. The line was to go to the right of this rock and catch the eddy on river right just below it. This eddy was a must make move to get ready for the middle section of the rapid.

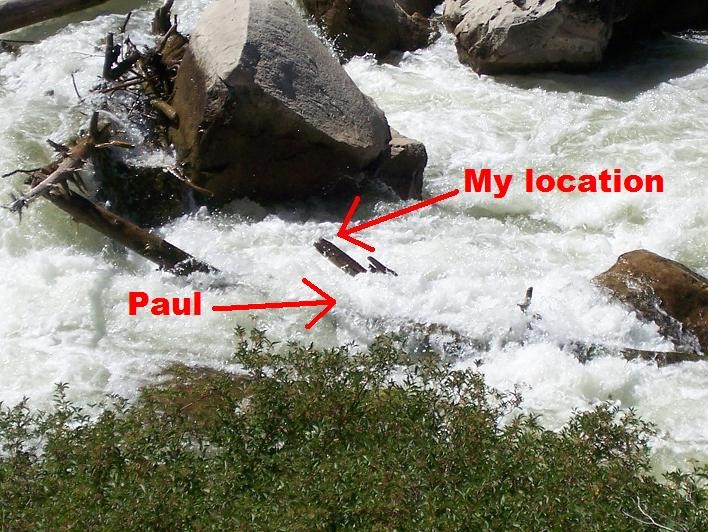

The eddy in river right (as seen above just below the boulder in the lower center) was so necessary because the middle section of the rapid was a log jam nightmare with wood traversing 95% of the river. The sneak route around the wood was to hug the right bank, duck under some bushes, and slip between some rocks to enter the third section of the rapid. However, to get to the sneak route, one had to first catch the above eddy.

The actual line down this section can not be seen as it is all the way on the right bank and underneath the bushes that block our line of site. The river left section is certainly runnable and not choked with wood, but is impossible to get to due to the upper section and where the water is pushing.

The third and final part to this rapid consists of setting up for and punching two giant holes. The second hole is around ten feet from trough to boil line.

After punching the second hole you can paddle around the third and the rapid is completed.

The scout and portage for this rapid is not easy as the banks are steep and composed mainly of chunks of sharp basalt talus rock. I made my way down to the bottom of the rapid to look at the bottom section first then made my way back up to the middle to have a closer look at the logjam. The sight I witnessed made me very uncomfortable. The truth is, this rapid is very runnable, providing the first part is done well. Like Jeff and Justin, I was leaning towards walking it but I hadn’t completely made up my mind. I figured, with all the whitewater ahead, this rapid would not make my day, but it sure could break it. That being said, I was waiting to see who ran it and how they did before making up my mind. Ken already had his boat on his shoulder and was carrying it down to the eddy just below the first section, so he could run the second half of the rapid. Paul was already on his way up to his boat to run the rapid. The only person Paul consulted about the rapid was Ken. Paul asked Ken about the first section, to which Ken answered, “it looks ok”, which it did. I know that Ken has regrets over not having said more to Paul about why he was portaging the top part. However, Paul did not ask, and I am of the opinion that the most convincing thing Ken could have said took the form of the boat already on Ken’s shoulder. We took our respective safety positions at various points next to the rapid. There I was, throw rope at the ready, positioned just below the critical middle eddy. Little did I know that I was about to witness and participate in the greatest horror of my life.

At this point my memory gets a bit fuzzy. Please excuse any discrepancies. I waited at my safety spot for five minutes before seeing Paul come into my field of vision. He was about at the second hydraulic in the initial chute. He looked good. This is when things went bad. It was either the second or third hydraulic that flipped him; from where I was standing I couldn’t be sure. He set for his roll as he cascaded down through these nasty hydraulics. I saw him pump twice while he was still coming down the initial chute. His rolls did not work; his boat was perpendicular to the current and his setup was on the downstream side; his paddle had no purchase. “Come on Paul, roll. Roll. ROLL!” I said to myself. He hit the slower water, just upstream of the logjam. I glanced just downstream of where he was; I saw in my mind the horrendous event that was about to take place.

Paul half-heartedly attempted his roll one more time, but failed. I saw the telltale sign of his boat twitching forward and backward. A sure indication that he was about to swim. I saw Paul’s head come up, and I watched in dread as less than a second later, Paul slammed into the logjam. The throw rope in my hands remained; useless. I was in shock; my brain was fried. “Oh no, oh no, oh no, oh no, OH NO! This isn’t happening. This isn’t fucking happening!” I thought. But yes, indeed it was happening. Paul was lodged between two logs that formed a V pointed downstream. Every couple of seconds I could see a flash of black from his helmet and a flash of red from his life jacket. His right arm was raised above the water level indicating that he was conscience. Paul’s head was under six inches of raging water. Ken, who was somewhere nearby, instantly tore off through the super dense ten feet thick layer of river willows that lined the banks. He was looking for, and found, a way to get to Paul. I climbed 15 feet up the bank, maybe for a better look, maybe to follow Ken. In truth, I didn’t know what I was doing. I turned around and went back to my original spot. At this point Ken was shimmying along the final log to get to Paul, and Jeff had joined me at my location on the bank. I don’t remember what Jeff was doing, but I asked him what I should do. He didn’t respond; so I said, “I’m going out there.” And I took off through the brush in a similar fashion to how Ken had done just moments before.

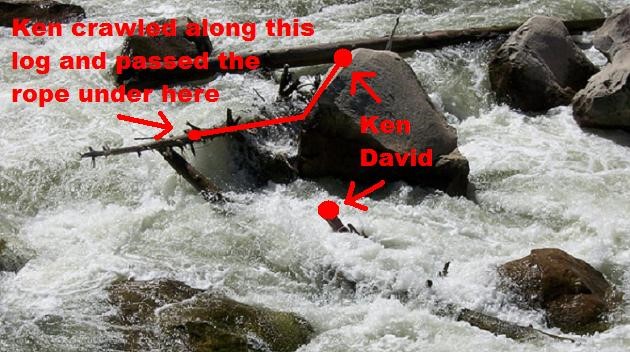

The way to get to Paul was not easy; more accurately it was fucking insane! The first move was to make a six foot jump from a rock to another rock then jump another eight feet into an eddy behind a boulder just upstream. After doing this, I grabbed the upstream rock quickly; before I was swept away and climbed up on it. The next move was to traverse eight feet of log that was covered with two inches of class five moving current. This brought me to a rock that was 20 to 30 feet from the river right bank and 20 feet downstream of Paul. From here I straddled the larger of the logs holding Paul and shimmied upstream towards Paul and Ken. I was scared out of my wits while doing this as the log I was on was covered with two to four inches of raging water and there were now log sieves just downstream of me on both sides. I’d be damned if I was going to let Ken struggle without help and Paul die alone. I must take a moment and thank Ken Ryan; I don’t know if I would have had the courage to go out there if Ken hadn’t first and demonstrated that it was possible. Going out there on that log is most certainly one of the salvations of my soul that I can take solace from. Now that I was out on a log with Ken and a stuck and rapidly dieing Paul, in the middle of a nasty class five rapid, the real work began.

Ken was on the log directly in front of Paul alternately trying to yank him up by his lifejacket and using a hand to try to create an air pocket for Paul to breathe under the six inches of water that poured over his head. Paul was still alive at this point. He was trying to help make an air pocket for himself and pull himself out by grabbing Ken. Ken told me later that Paul was responsive when he had arrived; Paul said a few things that were indistinguishable. Ken told me to try to get to the other side of Paul and make an air pocket while he tried to pull him out; somehow I managed to crawl around Ken and Paul and sit on the smaller log that was trapping Paul. I stayed on by hooking my leg underneath the log into some deadwood that was also trapped in the sieve. I brought my hands to the front of Paul’s helmet and tried to siphon the rushing water away from Paul’s mouth enough for him to breath. I could feel water splashing around between my hands. My air pocket wasn’t working. I felt like I was killing Paul. We changed tactics. Together Ken and I gripped the front and the back of Paul’s lifejacket and heaved. And Heaved. And HEAVED, until I thought I would fall off my precarious perch. Do to the nature of where I was sitting, with half my body in the same water that was trapping Paul, and nothing to push off of with my feet, I had no leverage, and could not lift with near enough force that I thought I should. I kept telling myself, “pull harder David; Damn it, Pull Harder!” At some point during these initial attempts Paul’s hand came up and briefly touched my arm. Then he lost consciousness; then he was gone. I did not realize that he had died at this time. While we were trying in vain to pull Paul free, his lifejacket began to slip up on his body. This scared me because I knew that without Paul’s lifejacket, there would be nothing to hold on to.

I wanted to cry. I wanted to fall apart and huddle in a ball. I knew something big was happening that would change my life. I didn’t know how to handle it. But every time I felt like I was close to breaking down, I steeled myself and shoved my fear and pain in to the back of the head. I had a job to do. Paul and my friends needed me now; there was time to break down later. After failing to pull Paul free, Ken suggested that we try to push him under the log. I was horrified, but without other options. I pushed him down with my hands, but I could hardly get him a foot below the water. Also I couldn’t lean over very far without falling into the deadly water that had trapped my friend. So I put my feet on Paul’s chest and tentatively stood on top of him. It was sickening. Paul would bob in the water a bit, but he wouldn’t truly submerge; he was beyond stuck. I suspect that there was no going underneath this log. I believe that the whole area in front of Paul was choked with debris from riverbed to water level. There was no “underneath”. At this point we received a rope from the bank. I don’t remember who caught it.

Justin and Jeff were on the bank at the ready, rope in hand. Ken quickly clipped the spectra rope to the closest shoulder strap of Paul’s life vest. Ken and I lifted together while Justin and Jeff pulled from the shore. Paul didn’t move an inch. We tried again, but I knew what we were attempting was futile. I called to the shore that we needed a Z-drag. I want to make clear how difficult it was to communicate with the bank. Even though they were, maybe, forty feet away, with the background noise of the water and my own head, it was very difficult to hear them. After the third attempt at communication, they understood me. It took a couple minutes for them to rig up the anchor and set up the rig. It was these periods of down time that were the worst. This is when my brain became active again and started to encompass the awfulness of what I was witnessing. We had long since stopped trying to create an air pocket for Paul. He had long since stopped moving. His head was clearly underwater as it had been for the past I don’t know how long. His body behaved like an extremely heavy rag doll.

The passage of time was extremely fast and at the same time crawled like it had nowhere to go. When the Z-drag was ready, Ken and I prepared to lift Paul. The Z-drag pulled and once again, Ken and I lifted. The men on the shore had the hearts of grizzly bears and they applied thousands of pounds of force to the line, and yet Paul still did not budge. I heard some yelling from the shore and I thought I heard Jeff say that they needed to cut the line. I found out later that we had snapped a spectra rope with a 2000 pound tolerance. The rope was cut and it hurried downstream.

“Rope!” Jeff said, and he threw it. I caught the bag perfectly as I sat perched on the end of my log. The impact of the rope almost knocked me off. I yelled at the riggers to move the Z-drag anchor upstream. The problem we were having with the Z-drag was not a problem of insufficient force; instead it was an issue of incorrect angle. We were attempting (due to a lack of other options) to pull Paul through a log that a tractor would have been hard pressed to move. I will try to illustrate.

The log that held Paul in place on our side of the river was placed at an angle nearly parallel to the current. Justin and Jeff, on river right, were able to increase the angle in the z-drag line to around 120 degrees to the current. However, since the log in question went past Paul upriver for another 10 feet, the shore team would have had to be directly behind Paul for this approach to work. This would have put them in the middle of the river. (Note: despite my poor artwork, six inches of water were flowing over Paul’s head at the time.)

Somewhere in the back of my mind I knew that our current approach would not work and that we had to do something else to get Paul free, but I had no idea what. I kept telling myself to think! Think of a solution! But none came to me. At this point Ken told me that he was going back to the shore to help Justin and Jeff with the rigging. There I sat, alone, on my perch, futilely holding onto the shoulders of my friend Paul. It was a strange feeling; holding him. He was completely limp now and the back of his neck was very pale. These moments when we were not actively engaged in freeing Paul were difficult; without action I had only thought, and my thoughts were not good ones. Soon the shore signaled me that they had the new rig set up and were ready to pull.

Within a few seconds of the new rig being set up I watched in shock as Paul’s life jacket began to rip off of him. I thought, “What the hell? Aren’t these things built to withstand these sorts of rescues?” The truth is that nothing is built to withstand a rescue like this one. I told the guys on shore to stop pulling, which they did. I needed some time to rig a piece of webbing around his chest. I thought briefly about how to do it when his chest was over a foot beneath raging water. The only thing I could come up with was a girth hitch. I knew that the applications of this knot in rescue limited to the use of setting up anchor and is never used to attach to a person because of it’s propensity to become too tight and injure the rescuee, but at this point I was desperate. I had no idea how long Paul was out and had no ideas what other way I could attach the webbing to Paul that wouldn’t come off or over his shoulders. All I knew is that we had to get Paul out quickly.

I was perched on the end of a two foot section of log.

I had my left leg dangling over the log on the same side Paul was. My right leg straddled the opposing side and was locked around my left leg to keep me in place. My left foot was somewhere underwater next to Paul’s left shoulder. I was actively pushing on him for balance. I leaned over as far as I could with the webbing in my hands. Try as I might, I could not get close enough to wrap my arms around Paul’s chest. Every time I would reach around Paul, the intensity of the water was such that I couldn’t even find my own hands. It is difficult for me to describe the precariousness of my position. I was fully aware that my location was neither stable, nor was my position dependable. I knew that if I fell into the water, my body would be pinned right behind Paul’s. It took me a few minutes, but I eventually secured the girth hitch. I did this by letting go of one end of the webbing, letting it float downstream, then reaching around Paul to grab it. When the hitch was secured, I carabined it to the Z-drag line. When that was accomplished, I yelled at the shore to pull.

I saw the error of my work immediately. The Z-drag was still clipped to Paul’s torn life vest. The tension on the line continued to pull on the PFD and not on the webbing around his chest as I had intended. Once again I yelled at the shore team to give me slack. After some reaching and more frustration at how much time the entire process was taking, I managed to unclip the PFD and clip in the end of the girth hitch. Once again I told the shore crew to pull. They pulled and suddenly there was an immense amount of tension on the line and on Paul. He didn’t budge an inch. It was like trying to pull him through the log that was holding him. Worse yet, as the tension increased, Paul’s left arm flopped up over his head and the girth hitch slipped over his arm and relocated around his neck. I had the sudden grisly image of watching Paul’s head get torn off. I screamed for the shore crew to stop.

Somewhere during these attempts the riggers on shore tried moving the Z-drag anchor upstream to achieve a more functional angle of pull. After spending more precious minutes readjusting the girth hitch, we tried again to pull Paul free. Again the girth hitch slipped over his arm. I leaned over once again to replace the girth hitch around Paul’s chest. This is when something weird happened. I fell. I was leaning over, trying unsuccessfully to reach around Paul. I was so tired. The fatigue weighed upon me like a heavy dark cape. All my movements were slow. My hands were shaking and I was cold from being splashed with the angry waters of the Blackfoot. As I was leaning over, my left leg slipped and came unlocked from my right leg. In slow motion I began to fall. I remember the frothy white surface of the water coming up to meet me. I thought “oh my god! I’m going in.” I was going to fall directly upstream and behind Paul. I was going to be trapped, not by the logs, but by Paul’s body. I was going to die. I reached out. Then, suddenly, I was moving away from the water’s surface. Then, I was upright and settled, on top of my log. I didn’t know what happened. I couldn’t think about how close I came to joining Paul or how I managed to avoid it. We still had work to do, and I was needed.

I don’t know if I called for help or the shore crew just realized that I needed help out there, but I saw Ken break away from the group and start the dangerous trip out to where I was. I was dazed from my recent brush with a watery death. I retreated from my log perch to the resting rock just downstream. I sat down; I was so tired. I wanted to lie down right there and sleep.

It wasn’t long before Ken got to where I was resting and the work began anew. I returned to my perch spot and Ken was just downstream of Paul and myself. We attached the girth hitch again and it was much easier because I was able to just hand the ends to Ken for him to wrap around Paul’s chest. We had Justin and Jeff, the shore team, pull once again. But again the incredible force of the Z-drag pulled on an object that was neigh unmovable and the strap pulled over Paul’s shoulder. I couldn’t figure out why this wasn’t working; the hitch should have held tight around his chest. But I could see that we had damaged Paul’s shoulder in the rescue. His arm was no longer sitting right at his side.

Ken and I had reached a point of exasperation. We had to get him out, and soon. I had some idea that he might somehow still be alive at this point. I was completely unaware of the passage of time. The truth is, I had known for a while of how to successfully attach Paul to the line, but it was too horrible to contemplate. I asked Ken, “Are we doing a rescue? Or are we now doing body recovery?”

“Body recovery,” Ken said.

“I know how to tie him,” I said, “grab his arms and hold his hands.” My heart was broken. I knew that by tying the webbing first around one wrist, then around the other, and finally tying both wrists together, the friction created would make it near to impossible for the knot to slip. I felt nauseous. I didn’t want to do this. I had pictures of Vietnam prisoners of war being hung from their hands in some dirty hopeless cell floating through my head. This was no way to treat a person; much less a friend. But dammit, we were out of options! What could I do? What could we do? I was desperate. Ken and I were efficient. We tied Paul well. He would not slip out this time. Again we told the shore crew to pull.

We encountered the same problem as before. The rope was trying to pull Paul through the log holding him in place. Only this time Paul’s arms were being violently pulled over the log. Ken and I tried to lift Paul vertically while the shore team pulled. It was like trying to lift a Buick. My mind reeled as I watched Paul’s arms be nearly torn from their sockets. I yelled for the shore team to stop pulling. “What do we do?” I asked Ken, “This will not work. We need to change the direction of travel of the rope.”

“What if we could get the rope underneath that log instead of over it?” Ken asked.

“I don’t know, maybe,” I said with exasperation.

Ken surveyed the river and the placement of the rocks and said, “Let’s try it.” Then he took off. Ken was fearless in the way he jumped from rock to rock and rock to eddy. I don’t think I could have done what he did. This was his path.

Ken got to the rock upstream of me and I unhooked the line to Paul and let it float downstream. The shore team pulled the line in and threw it to Ken. Ken fearlessly crawled out on a log that was perhaps four inches thick and directly upstream of Paul and the hydraulic forces that had crushed him. Ken then fed the throw rope under this log and presented us with a new vector of pull with which to attempt to dislodge Paul.

Ken tossed me the rope and I carabined it to Paul’s tied wrists. I yelled at the shore team to pull again and while Ken made his hazardous climb back to our position, I waited in anticipation for the results of this new approach. It was sickening. The ease at which Paul came free defied the intense labor that the four of us had spent the last hour engaged in. I had pulled on Paul to within an inch of my life; I was mentally and physically exhausted and I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. But by getting the Z-drag rope underneath the river right log that held Paul, he came free so effortlessly that the Z-drag was probably not necessary.

Paul’s body came out, pulled upstream, and began to pendulum to the shore. I remember standing on my “resting rock” and watching the spectacle, all emotion drained from my being. He appeared to move through the water like he was flying with his arms outstretched in front of him, or perhaps like a sturgeon, hooked, and being pulled in. I could see how pale he was, even through the water. Paul was naked from the waist down. The force of the water had removed all of his clothes, his booties, and over the course of the rescue, even his life jacket. The only thing he still wore was his paddling jacket. I marveled at the strength and callousness of the river. I sighed with relief and began the perilous crawl back to the river bank. Now that the urgency of saving my friend was passed, I was terrified of where I was in the river. I hesitantly made the moves that I had to make to get back. I didn’t feel capable of maneuvering myself to shore, but I knew that there was no rescue for me; there was no other way to get to shore then by my own strength and agility.

As I closed in on the river right bank I heard a commotion coming from the other rescuers. The operation was not over, Paul was not yet free. I sighed in exasperation, my strength was failing me. When I got to the right bank, I saw what had happened. With no flotation on Paul, he had sunk to bottom of the river. As Paul was swinging to the right bank, the rope he was on had gotten caught beneath some rocks. Paul wasn’t more than twelve feet from the bank although we could no longer see him. I could see the rope emerge from the water perhaps five to ten feet up river from Paul. I began to have desperate thoughts at this point. I just wanted this to be over. We had worked hard, we deserved for this to be over. I seriously entertained the idea of jumping in to where Paul was and grabbing the rope up stream of him. I knew I could free him this way. I knew it! Then I could ride the rescue rope back as it swung to shore. Better sense prevailed before I acted on this thought.

The riggers attached a carabineer and a second rope to the taught line that ran to Paul. Ken dared to return to a position close to where we were before. Ken was on the river left side of Paul and able to apply a perpendicular pull to the rope holding Paul. The stuck rope came free immediately and the riggers guided Paul to an eddy near me. Paul was face down bobbing in the water. I seem to recall Ken throwing Paul on to his back and lifting him, while I tried to help by lifting Paul’s legs. Paul’s skin was the color of white canvas; his flesh had the feel and look of plastic. We got Paul onto the bank and turned him over. The ravages of the rescue were plain to see. We had abused poor Paul significantly while trying to get him out. Dark purple bruises lined his wrists arms and shoulders. Paul had cuts on his face and neck. He lay there on the black basalt rock, surrounded by dark green brush with his eyes open; lifeless and staring at nothing. I was overcome by an intense morbid curiosity. I poked at Paul a couple of times. I am not sure what I was seeking by doing this. His flesh felt hard but malleable. It was kind of like poking plado or silly putty. I had to restrain myself from any further displays of my strange curiosity.

Ken was discussing ways of getting Paul to the top of the canyon when Justin said some very simple, but powerful words, “It’s ok to ask for help. We have done well. We got him out and to the bank of the river. It is ok to ask for help now.” Ken and I were reluctant to pass this job onto anyone else. Justin continued, “You two were inspirational out there. No one could have asked more of you. It is time to get help.”

Thus began or painful and silent journey to the top of the canyon. This was no easy physical task for the canyon walls loomed 500 feet above us. The trail out consisted of climbing a steep talus slope to the canyon rim. Sharp unstable rocks combined the with the unworldly fatigue that we all felt made the trip out surreal and dangerous. We decided to take our boats and gear with us on the climb. It was grunting; it was struggle; it was slow. Justin lagged behind as his damaged ankle had been more than overworked this day. I felt energy high within me that I didn’t quite know how to handle. I knew that so long as I stayed busy and suffered through physical exertion I wouldn’t have to think of the day’s horror. As soon as I got my boat near the top I ran down to help Justin with his. When all the boats were at the top, the day, which had moved so quickly up until than, slowed to a crawl.

The put-in truck was retrieved and we drove to a place where we could get cell service to call search and rescue and our respective loved ones. I wanted to call my father and go through the complete mental break down that I had sought since the accident, but Justin wisely warned me that it was not yet time for that.

Search and rescue showed up in the form of one fat sheriff. We told him that we needed 12 strong men and a backboard, but he couldn’t take our word for it. (Despite the fact that we were the most qualified swift water rescue team assembled in all of eastern Idaho) The fat sheriff had to go look, then he called his boss who had to go look. We were offered the choice to help bring Paul’s body to the canyon rim or to return to Pocatello to bring the news to Paul’s wife. The obligation that we felt was to not leave a man behind. We elected to stay. Finally about four hours later we were back on the canyon bottom with 12 strong men and a metal stretcher. I remember laughing when a few guys from the search and rescue team were freaked out by a rattle snake near Paul’s body. I took a stick and shooed it away. I still felt like I hadn’t done enough; I still felt like I had failed; failed Paul, failed my companions, failed myself. I needed to do more. Everyone present rotated in and out of the different carrying positions on the stretcher. My muscles burned and my joints ached, but I never left my position. I remember feeling that the Search and Rescue guys were a bit too jovial and upbeat for my liking. When Paul’s body was at the rim, we left.

I drove back to Pocatello with Ken. He agonized over not saying something to Paul when they passed each other while scouting the rapid. I reaffirmed that it was Paul’s decision and not his fault, but I knew it would haunt Ken for a while to come. As we approached Paul’s house and the impending encounter with his wife, I began to get nauseous. What would I say to her? How should I act? Would she blame us? As the left turn approached, I felt a burning urge to yank the steering wheel to the right or to ask Ken to stop and drop me off. But I did not, and soon we were parked. The four of us got out of the trucks and turned towards Paul’s house. At that moment, every fiber of my being wanted to be somewhere else. I steeled myself internally and began to walk across the street. It was the hardest thing I have ever done.

Afterword

The most common question I hear when I tell people about this story is “Why are you writing it?” The short answer is Honor. Honor to Paul and his final struggle on this earth; honor to my brother rescuers who risked their lives to save a friend who was unsavable; honor to myself. This is a story worth telling; an educational look at river rescue combined with an intense look into some of the driving forces that emerge when life and love are on the line.

I began to write this story as part of a cathartic process intended to help me heal and find closure. As time passed, I visited this story less and less. In the end, however, I decided that, among a lake of unfinished projects, if I am at all to be a man of conviction, this project would be completed.

What have I learned from this experience? I have learned that I am a good man to have in a bad situation. I have learned that sometimes all the strength, training, and effort of man cannot prevent the inevitable. Before this event, I thought that if I was truly committed to an outcome of an event, I could make it happen. I truly thought I would be able to save Paul that day. I was wrong. On this day I learned about pain, not my pain, but Lee’s, Paul’s wife. The agony of loss I have seen in her eyes frightens me. I have not felt this pain, nor do I wish to. I am humbled by it. Some of the other things I’ve learned just can’t be put into words.

I hear Paul talking to me from time to time. When I perceive some misfortune in my life and start feeling sorry for myself, I hear his Polish accent saying, “I think it’ll be ok.” There is a smile in his words and the utter belief that they are true. That was how Paul was; the positive outcome of every situation Paul found himself in he absolutely accepted as fact. Paul was an amazing man. He gave all of himself to anyone he happened to be with. He was a world class cardiologist and an even more incredible husband, friend, and son. Paul Abraszewski’s life was a life worth remembering. I think his death is worth remembering as well.

Dedication

In memory of Paul—Thank you for teaching me how better to live.

To the rescuers—Heroes…

To Lee—No one can say why we must suffer so in this life. I will always be there to help.

Abstract

Experiential learning is a fundamental learning process for humans that begins when we are born and learn to use our hands, speak, and walk. Experiential learning helps foster student passion and deeper understanding of abstract subjects. There is a movement in America to make education more experiential. This is represented by new pedagogical practices of inquiry learning and project based instruction. Outdoor programs such as NOLS and Outward Bound have been using wilderness based experiential learning programs to help students develop qualities that will help them throughout life. Some of the transferable skills of wilderness based experiential learning include leadership, group dynamics, resilience, self-esteem, the ability to make decisions in difficult circumstances, and respect for the natural world. These qualities, nurtured in students, will help them social and academically at school, as well as with their professional goals in the future.

Rationale

Experiential learning is the process of making sense from varied experiences. Research has shown experiential learning to be a highly effective progressively driven educational technique. It is also the fundamental pedagogical theory behind outdoor adventure programs such as the National Outdoor Leadership School and Outward Bound. Expeditionary Learning, experiential learning, and other progressive schools have operated successfully in the United States for decades, but mainstream high schools have little innate curriculum that is either experiential or wilderness based. The schools that persevere using the structure of experiential learning use real life scenarios to drive student interest. In most cases these schools also have alternative sources of funding, community support, and certain leeway regarding standardized testing. There are educational benefits to using wilderness based experiential education and the general use of nature as a supporting role in formal education. The real question is what are the characteristics that separate successful students from those who struggle in school? Furthermore, can these characteristics be cultivated though experiential learning in nature and then be applied to the classroom setting?

Students struggle to learn in formal school settings for many reasons including boredom, lack of confidence, learning disorders, behavioral and emotional troubles, and difficult home lives. Experiential learning in the wilderness may not be able to solve all these problems, but it can help students to significantly reduce some of them. Boredom, for example, is a symptom of disinterest. Students who are not interested in the material at hand will have difficulty absorbing that material. “The brain optimizes input by actively resisting meaningless (boring) information, preferring to search for new, interesting experiences which can be integrated into existing structures” (Allan, McKenna, & Hind, 2012, p. 7). Students’ brains shut down when faced with the same curriculum taught the same way day after day. In a progressive styled approach, simply changing the curriculum to include community projects that the students are interested in can be enough to engender greater interest in learning. Taking students out of the classroom into a natural setting is another way to change the learning format. The natural setting needn’t be far from school. Lessons can be taught in the school yard or at a nearby park. Furthermore, if the subject of the lesson has to do with the natural world, of which the students are a part of, then student interest will increase. However, greater student interest is only a small part of the overall student character that can be cultivated through wilderness based experiential education.

The skills learned during experiential learning wilderness courses can be grouped into four main categories: self-systems, group dynamics, personal values, and technical skills. Wilderness based technical skills are not particularly useful for the purposes of engaging students, since the use of these skills is limited to time spent in the backcountry. However, the skill characteristics within the other three categories will lend themselves to developing more emotionally healthy and motivated students. Self-systems include the skills of self-confidence and self-concept. Both self-confidence and self-concept are hugely important with regard to a student’s ability to persevere with academic challenges and to maintain emotional balance throughout the demanding process of learning. Personal values, which include spirituality, environmental ethics, and social justice themes help students to define their own morals, their connection with the world, and their personal motivations in terms of what social or political causes the student will endeavor to champion in their lifetimes. Group dynamics, which includes the ability to work with others, is an invaluable skill in school and even more so in the professional world.

Group dynamics - a skill set with many positive benefits in both the academic and professional world - is richly improved through outdoor experiential education. Historically it can be argued that very first teacher of group dynamics, language, and social order, resulted from individuals exchanging knowledge on how to survive in ancient grasslands in a world of predators (Allan, McKenna, & Hind, 2012, p. 7). A similar type of necessity can be artificially created through wilderness adventure or challenging experiential learning projects. A compliment to these skills, and equally important to academic and professional success, is the cultivation of psychological resilience.

Resilience is an individual’s ability to adapt to stress and hardship (What is Resilience?, 2014). Resilience comes from an “interplay of personal and environmental factors rather then a single quality or set of traits. It is a multi-dimensional construct made up of individual assets and resources which reflect relative strengths in emotional and cognitive competence, social connectivity and physical capability” (Allan, McKenna, & Hind, 2012, p. 3). Students of any age are exposed to pressure to perform in school and many students are exposed to large quantities of stress as a result of troubled home lives. The mental suffering resulting from stress can lead to social and emotional difficulties, misbehavior or lack of motivation in school, and self-destructive behavior such as drug use. It seems self-evident that a student who is abused at home is unlikely prioritize their math homework over the mechanisms of mental preservation they have created. This is an extreme case, but a large spectrum of behaviors can result from stress. What we seek to do as educators is offer students better tools to deal with their stress and hardship so they can perform better in the classroom and make sound decisions in their lives. Psychological resilience is an umbrella term which encompasses many characteristics that make students more successful.

There is a link between resilience and outdoor experiential based education. (Allan, McKenna, & Hind, 2012, p. 3). The multi-sensory nature of outdoor environments, as opposed to the monotonous nature of a typical classroom, has a profound effect on the brain’s ability to adapt to new and challenging situations (Allan, McKenna, & Hind, 2012, p. 5). People who learn in multi-sensory environments are shown to perform better in a range of cognitive and physical tasks then those who learn in uni-sensory environments (Allan, McKenna, & Hind, 2012, p. 5). This isn’t to say that students need to be thrust into the wild to find a multi-sensory environment. Educators can cultivate a multi-sensory environment in the classroom by changing the nature of the educational process to include experiential lessons based on real life scenarios and challenges. Of course, if the teacher takes the class outside of the classroom, even to a local business or park, the multi-sensory input of the lesson is dramatically increased. As multi-sensory input is increased in the learning process, so then is psychological resilience. Whether it is resilience, self-esteem, or group communication, wilderness based experiential education regularly results in students cultivating skills that will help them during formal education and their lives beyond.

Evidence

The majority of the evidence surrounding the benefits of wilderness based experiential education are anecdotal or based on self-applied questionnaires. This is problematic from research perspective, however, the quantity of evidence in this area, despite being anecdotal, is indisputable. In the area of self-systems, which include confidence, efficacy, and self-concept, one study from NOLS found that self-efficacy was dramatically increased from their baseline levels immediately after their course as well as one year later (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 88). Increased self-awareness is also reported to be a highly transferable skill resulting from outdoor education (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 88). Another study, with a sample size of 485 participants, reported that 57% of participants gained perspective on how life can be simpler, 41% felt they function more effectively under difficult circumstances, and 37% believed they had new skills with which to function in a leadership role. The ability to function under difficult circumstances might help a student study during finals or to be able to separate a challenging home life from the need to continue learning while at school. Other beneficial skills such as courage and boldness are also gained through outdoor experiential education.

Another study, with a sample size of 296, showed the majority of participants in an outdoor education course felt “pronounced impacts on aspects of taking action and decisiveness including risk-taking, boldness, initiative, and clarity of thought” (Kellert, 1998, p. 45). The same study indicated positive effects for the majority of participants on self-concept, self-esteem, self-respect, inner calm, and optimism. The positive effects were still reported in the follow-up query six months after the course (Kellert, 1998, p. 45). This study also noted sustained improvements in seeing tasks to completion, taking action, problem solving, making difficult decisions, delegating tasks, and leadership (Kellert, 1998, p. 48). Problem solving, perseverance in the face of adversity, and leadership are all qualities of a successful student. If these characteristics can be cultivated as a part of the formal learning process in a high school, students will benefit and are likely to have more success in their academic endeavors. Students’ abilities to work together also play a large role in their capacity to succeed as students and a professionally later on. Fortunately, the skill set of group dynamics is one of the skill sets most enhanced by outdoor education.

One study involving sending out a follow up questionnaire to 950 participants two years after the conclusion of their programs. Based on that questionnaire, the study asserted that “awareness of others and interpersonal skills were outcomes transferred from Outward Bound courses to life post course” (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 88). Another study looked at the results of a corporate adventure training program and found that trust, collaboration, communication, decision making, and task completion were all attributes that were enhanced and perpetuated a year after the course was completed (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 88). In that same study, with 296 participants, the majority reported, six months after the course, that they had acquired many skills that transferred to the workplace including leadership, group participation, interpersonal skills, and conflict resolution (Kellert, 1998, p. 48). Interpersonal skills is a huge factor in determining a student’s success at working with others on a school project or collaborative learning.

The development of personal values may be slightly less applicable to academic learning, but it is important for young people to find their place in the world. That is to say, what do they fundamentally believe in? These personal beliefs will set the tone of their future choices concerning work, environmental impact, and even their spiritual beliefs. In one study of 288 participants, student responses indicated that they felt significantly more responsible for their local and natural environment as a result of their outdoor educational experience (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 89). In a small case study, five participants maintained a commitment to personal activism for over three years after the course (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 89). In an aforementioned study, involving 296 respondents, the majority reported an increased desire to spend time in nature, an inclination to reduce waste and litter, and feelings of spiritual connection and humility towards nature. (Kellert, 1998, p. 40). It is difficult to gauge what effect an increased connection with nature will have on the academic abilities of a student, but consider that we are not just trying to create better students through outdoor experiential education, we are trying to create better people. We want students who not only persevere in school projects, but also feel a connection with the world they live in. These students are more likely to be social and environmental activists. These students are more likely to be driven to change the world we live in to make it a better and more responsible place, and they are more likely to possess the skills to succeed.

Concerns

There are a couple of main concerns surrounding the incorporation of outdoor experiential education into a formal school system. The first concern is the nature of the research itself. The second concern focuses on the transferability of soft-skills in terms of how we know that students are learning the skills that will make them healthier students while engaged in an adventure course. And last, from a logistics standpoint, a class trip into the wilderness costs money and requires additional staff with a different set of expertise than is commonly possessed by high school teachers.

The benefit of outdoor experiential education is difficult to research. The sample sizes are often too small for rigorous studies and the larger studies are often based on questionnaires filled out by the participants months or years past the date of the course. This is problematic because testers may lose significant data based on who chooses to respond and who doesn’t. I might argue that only those who had a positive experience on their wilderness course and subsequent life choices would take the time to fill out and mail a questionnaire about their experience. A further complication is the fact that the same people who report how the skills they learned on their course have impacted their lives have also had other life-changing experiences between the time of the course and the time of the questionnaire years later. It is hard to accurately gauge which skills came directly from the course and which skills were learned after the course. That being said, there is research surrounding what skills do transfer, but there is difficulty in ascertaining the magnitude of the particular skill transfer (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 89).

Mezirow, an American sociologist from Columbia University, defined the concept of Transformative learning. Transformative learning is defined as creating a “deep cultural shift in the basic premise of thought, feelings, and actions” (Kitchenham, 2008, p. 104). Transformative learning comes about when a student’s current experiences are at odds with their old knowledge. Their minds search for a way to organize the new information to make it fit in with the previous constructs of the old information. As this process occurs, learning takes place (Amato & Krasny, 2011, p. 239). Transformative learning begins with a bewildering dilemma, which is followed by critical self-reflection, social interaction, and the formation of a plan of action. The success or failure of the plan of action leads to the formation of new roles and understandings (Amato & Krasny, 2011, p. 239). I posit that experiential education brings about transformative learning by creating scenarios where previously held knowledge conflicts with new information. This might happen during an experiential learning project near school and it will definitely happen when students are faced with the rigors and challenges of the wilderness. There is much anecdotal evidence surrounding the transfer of skills from a wilderness based experiential course. Researchers have seen this as evidence of transfer, considering that students who have participated in wilderness based education have reported and shown evidence of the enduring qualities of these new skills (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, & Gookin, 2009, p. 87).

The final concern of logistics and funding is a real concern in a typical high school run by the state. Some state run schools have a lot of extra money donated by parents to be used for extra programs for the students or better facilities and resources. But many community high schools lack the support of parents or the parents lack the wealth to contribute to the school. In other words, any school that incorporates wilderness based experiential education must have additional funding, above and beyond what is doled out by the state. There are examples of alternative high schools in the United States that incorporate these types of programs into their curriculum. Most of these schools are private or have alternative source of funding. Eagle Rock School is one such example. Eagle Rock is completely free for its students and 100% funded by Honda. It is possible to find funding for individual schools that are interested in shifting to include elements of outdoor experiential education. And some experiential education is not expensive, like a walk to a local park. However, there would have to be a cultural shift in America towards funding education if every school wanted to add experiential outdoor education to the curriculum.

Implications

These findings are important because of their potential to change the learning process taking place in our current educational system. In some cases students are getting an excellent academic education without any type of experiential education, in other cases they are not. However in both cases there is a question as to whether we are teaching students how to incorporate their learned knowledge in responsible, relevant, and practical ways (Kellert, 1998, p. 75). Furthermore, one might argue that our nation’s youth is facing a crisis of values. Family and community connections are eroding which can foster a sense of rootlessness and declining civic participation (Kellert, 1998, p. 75). Wilderness based experiential education is shown to be successful at reconnecting young people with nature and their responsibility to protect and improve their natural and home environments. Additionally, any experience which is revealed to develop character, responsibility, confidence, and optimism are potentially important for student success in school and beyond.

The educational approaches of high schools in America are diverse in many situations. However, there are a few generalizations that most American high schools fall into. Most high schools emphasize abstract and non-experiential learning. Most high schools stress specialization within each discipline. That is to say that different course subjects are segregated from one another. Last, most high schools provide little opportunity for outdoor education (Kellert, 1998, p. 76). Outdoor components to educational programs provide the opportunity to bring experience and connectedness back to the learning process. This doesn’t have to happen hours away in a national park. The natural environment is everywhere and can be found close to most every school.

Of all the characteristics learned in a wilderness based experiential course, leadership, teamwork, and self-confidence are perhaps the most important for students to be successful in school and beyond. These are characteristics that are required for high academic achievement, but at no point in a regular high school curriculum are they taught. This paradox can be solved by implementing some aspect of outdoor experiential education in the mainstream learning process. Even a small outdoor experiential program could yield huge benefits for students. Nature is an intrinsically powerful tool for growth and maturation. At a time when we as a people have become increasingly insulated from nature, and when large demographics of students are struggling to connect with the current format of high school education, the solution may be a return to the lessons of the natural world.

References

Allan, J. F., McKenna, J., & Hind, K. (2012). Brain Resilience: Shedding Light into the Black Box of Adventure Procesess. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 3-14.

Amato, L. G., & Krasny, M. E. (2011). Outdoor Adventure Education: Applying Transformative Learning Theory to Understaning Instrumental Learning and Personal Growth in Environmental Education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 237-254.

Kellert, S. R. (1998). A National Study of Outdoor Wilderness Experience. New Haven: Yale University.

Kitchenham, A. (2008). The Evolution of John Mezirow's Transformative Learning Theory. Journal of Transformative Education, 104-123.

Sibthorp, J., Furman, N., Paisley, K., & Gookin, J. (2009). Long-Term Impacts Attributed to Participation in Adventure Education: Preliminary Findings from NOLS. Research in Outdoor Education, 86-103.

What is Resilience? (2014). Retrieved from American Psychological Association: http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx